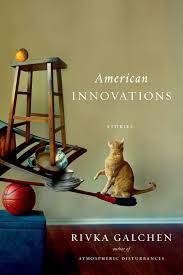

Rivka Galchen: Canadian-born, Oklahoma-raised, New York City-dwelling author of a novel (Atmospheric Disturbances), a collection of stories (American Innovations) and the forthcoming Little Labors (New Directions, 17 May 2016). Her style is something of the whimsically eerie and she is one of those great writer’s writers who likes to be fairly clear (while also a bit mysterious) about what literary influences are swimming around up there in her imaginary.

Rivka Galchen: Canadian-born, Oklahoma-raised, New York City-dwelling author of a novel (Atmospheric Disturbances), a collection of stories (American Innovations) and the forthcoming Little Labors (New Directions, 17 May 2016). Her style is something of the whimsically eerie and she is one of those great writer’s writers who likes to be fairly clear (while also a bit mysterious) about what literary influences are swimming around up there in her imaginary.

Here are my notes on a thing – the toilette – in Rivka Galchen’s American Innovations.

The way that Galchen describes the “toilette” – or, what most people think of as getting dressed and making oneself look as presentable as possible – has to be the most perceptive and true depiction I’ve ever come across. There are a few passages in the collection about looking in the mirror or about scaling the odd bumps and curves of feminine territory with the trappings of contemporary style that I read over, and over, and over again. I read them aloud to my husband saying, “Honey! This is IT! This right here. This is what it’s liiiiiike!”

This is what I’m talking about, a scene of getting dressed from the very first story “The Lost Order”:

“For a while it was my conviction that pairing tuxedo-like pants with any of several inexpensive white T-shirts would solve the getting dressed problem for me for at least a decade, maybe for the rest of my life. I bought the tuxedo-like pants! Two pairs. And some men’s undershirts. But it turned out that I looked even more sloppy than usual. And by sloppy I just mean female, with curves, which can be OK, even great, in many circumstances, sure, but a tidy look for a female body, feminine or not feminine, is elusive and unstable. Dressing as a woman is like working with color instead of black and white. Or like drawing a circle freehand. They say that Giotto got his job painting St. Peter’s based solely on the pope’s being shown a red circle he’d painted with a single brushstroke. That’s how difficult circles are. In seven hundred years since Giotto, probably still–”

Reading this, my first thought was that Rivka Galchen used my closet for research. I own those tuxedo-like pants. I own those T-shirts. I too had grand illusions about how they would solve the getting dressed problem for me. They did not. My second thought was, Why is this a problem? Why is getting dressed as a woman so problematic? Because we are meant to be both tidy and free. Angular but soft. Flowing but controlled. Our wardrobes and general appearance are supposed to encompass both the yin and the yang. We are meant to show whatever curves we have, to (ex)claim them forthrightly, but they had better be properly tucked in.

This short phrase – “And by sloppy I just mean female” – I would invite everyone to take that very seriously. Don’t be offended by it. Don’t dismiss it as whiny. Just take it seriously for a second. We abhor sloppiness in female dress but most of what we consider sloppy is simply the femaleness of women showing through. Brassieres are a problem. The straps are wont to stick out. If they do not fit perfectly there are the undesired (and undesirable perhaps) traces of bosom. Static is a mortal enemy because static shows the outline of legs. This is why the invention of leggings was such a breakthrough. It enabled us to look at women’s legs without having to actually look at women’s legs. Hairstyles are another issue. Hair must be fairy princess long, but must also be kept tidy.

Sloppiness is part of a growing trend for young women. The messy bun. The leggings and oversized T-shirts. The neon bras under large translucent blouses. It’s an interesting development. Yet we hate it. And no one would ever go so far as to wear these things out into “the real world” of social and professional interaction. Of course!

Galchen’s story as a whole does not announce a feminism of any specific variety. One doesn’t have the impression that she is making a clear “statement” about what it is like to be a woman who must get dressed every morning and go out into society. No grappling with “what does it all mean?” and the like. But I’m caught up in this sartorial point. The narrator assumes that if she simply dresses in men’s clothing, the “problem” of having to dress as a woman will be solved. She is unsuccessful because these garments do not fit. But women’s clothing doesn’t quite fit either. Because it is not made to fit. It is made to be ridiculous. It is made to be a failure and to make failures out of women.

That is why the comparison to drawing a circle freehand is so fantastic. Who can perform this feat but a great artist? And a man, at that.

Aside from all my snark about women’s fashion spurred on by this passage, Galchen is saying something significant in this story – a riff on James Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” – which she discusses in an interview with Harper’s. She claims that she was interested in the kinds of fantasies that are open to men, as opposed to those that are open to women. Walter Mitty is of course the story of a man who leads a very dull life but imagines himself performing very adventurous – and masculine – feats. The narrator of “The Lost Order” when alone and bored, imagines different ways of dressing. Galchen says in the interview that the story didn’t turn out quite like she planned, but I think she makes her point. It wouldn’t have to be about clothes. It could be about something else that represented gender roles. (Oh yeah. PS. This whole discussion of clothing is actually a way of expressing dissatisfaction with the binary choice between gender roles.) Not only are actual lives territory for gender inequality, the wildest fantasies of those lives, the fantasies of our own potential, are subject to the same inequalities.

The second passage that I underlined several times and reread many more comes from the title story. Again, we see a female narrator who has a bit of time on her hands, who reflects (this time literally) while performing the “technologies of the self” largely associated with women:

“In the bathroom, I washed my face with peach scrub and took care, as I generally do, not to look into the mirror too gesamtkunstwerk-ily. Instead, only in close patches. Only enough to rest reasonably assured that nothing too grotesque has overnight arrived on or departed from my face, and that I have scrubbed away all the applied scrub. It’s important to avoid mirrors if one is unprepared to accept their daily news, and I think, in something as insignificantly devastating as appearance, denial is more socially constructive than despondency. Not that there’s anything especially wrong with me – just the usual.”

There is so much going on here. For the purposes of the story, what’s significant is that the narrator is attentive to what may appear or disappear from her image. I don’t want to give it away, but this story (and actually all of the stories in this collection, more or less) is about a substantial corporeal intrusion. But there’s kind of a Heisenbergian uncertainty toward the face that extends toward the self more generally. One may closely examine one’s person or life, but only in small sections. Only piece by piece.

(Forgive me, the Heisenberg comparison doesn’t quite work. But it does almost so I am keeping it.)

The narrators in this collection are frustratingly unreliable. And this passage gives a clue as to why. It’s not a question of ignorance, it’s a question of being able to see only certain facets at once. Of picking the patches of their lives that they are willing (or able) to trouble.

But again we have this tone regarding the appearance: “Not that there’s anything especially wrong with me – just the usual.” As though it is the most normal thing in the world to have something “wrong” with oneself. Like the narrator in the other story, declaring completely without irony but with only a slight undertone of spite that “sloppy” simply means “female” as though this were an idée réçu we all share. In point of fact, it is. Similarly, it is a kind of universal truth that if one is a woman in front of a mirror, there is (or will be) something wrong. Yet, of course, it is not “socially constructive” to pay too much attention. To have feelings about it.

This theme – denial as a kind of socially constructive behavior – can be traced throughout the collection. But there is something so perfect about presenting this theme in terms of the face. Any undesirable inconsistencies of the face are “insignificantly devastating” (a luminous oxymoron if I’ve ever read one) but at what point does an intrusion upon the self because significantly devastating? In many ways, that is the question that this book asks. At what point – between a zit and a divorce – does the continual shapeshifting of life become significant? None of the narrators seem to have answers to this question, but their continual denial – of people, of events, of things – is a magnified form of this moment in the mirror. Denial of the self is pervasive in the book, but it is also an intimate view of how women deny their selves more broadly within society.

Leave a comment